Up the Gatineau! Articles

The following article was first published in Up the Gatineau! Volume 51.

Article disponible en français

Settlement of the Township of Low: The 1850s

Martin Lamontagne

In 2002, Martin Lamontagne bought a property on Martindale Road in Low, a rural municipality halfway between Gatineau and Maniwaki. Over the years, as Martin restored his century-old home, he learned about the property’s original owners, the Kilcoyne-Sweeney family, Irish immigrants who had settled in Low in the mid-1800s. He was drawn into a quest to explore and document their history, as well as the history of the house, the property and the township in its early days. His research culminated in his recently published book, The Story of an Irish Pioneer Family, Low, Quebec – 1850–1925.

The following article is an adapted and abbreviated version of the book’s chapter on the 1850s focusing on the settlement of the Township of Low. Readers can refer to Volume 50 of Up the Gatineau! for another adaptation from this book, on early settlement of the Upper Gatineau Valley in the 1840s. Originally written in French, the English translation of this article in Up the Gatineau! was done by the author.

By the 1850s, the rate of settlement in the Gatineau Valley (and the entire Outaouais) was gaining momentum, spurred on by the active logging and timber industries. The first signs of settlement in the then-unnamed Township of Low dated back to the mid-1830s, when the lumberjacks of the associates Hamilton and Low were logging around the Paugan Falls. The first permanent settler was Caleb Brooks, who arrived with his family in 1837. At least 20 other individuals and families followed during the 1840s.

The first census of the township was conducted in January 1852.1 The population was reported as 272 individuals—about 50 families2—occupying almost 5,000 acres, of which about 20 percent was under cultivation. Almost all were originally from Ireland, with the remainder from Scotland, the United States or other parts of Canada. This was the genesis of the municipality that we know today as Low, which the census takers, Caleb Brooks and David Knox, commented on as the “poor town ship of Low.”3

Among those 50 families were Anthony Kilcoyne and Mary Sweeney, with their three children: Bridget, Mary and John. This is the family that made the property at 356 Martindale Road what it is today, although they first lived on the adjacent property.

The Kilcoyne-Sweeney family had likely arrived in the township in 1846 or 1847, based on an 1845 family baptismal record in Ireland. The first record of their presence in the Gatineau Valley appears in August 1848, in the register of the Parish of St. Stephen in Chelsea for the baptism of their daughter Mary.4

After an arduous voyage across the Atlantic, this family and other newcomers would have journeyed up the St. Lawrence River to Montreal (about 300 kilometres), and then to the Township of Hull via the Ottawa River (about 200 kilometres farther) to arrive at the mouth of the Gatineau River, opposite Bytown (now Ottawa).

They would then have had to venture into the heart of the forests of the Gatineau Valley, a further 50 kilometres. There was no stagecoach service, and the route to Low was a shanty road built by timber merchants. It was mainly only passable in the winter, slow and dangerous in some places, and strewn with obstacles: stumps, stones, rocks, muddy and swampy land, and innumerable unbridged gullies and streams.

It likely took three or four days of sustained effort for newcomers to reach the Township of Low— to discover what? One or two hundred acres of woodland, partially stripped of its largest trees by the timber merchants, with no house to accommodate them, no stables or barns for livestock and produce, let alone any parcel of land ready for cultivation. They likely felt disappointed and alone in this sparsely populated hinterland.

Like all newcomers then, they had to face many other challenges: the rigour and length of the winters, the difficulties of travel, the isolation, and the scarcity of medical help or religious support. Illness, difficult childbirth and accidents must have been among their greatest fears.

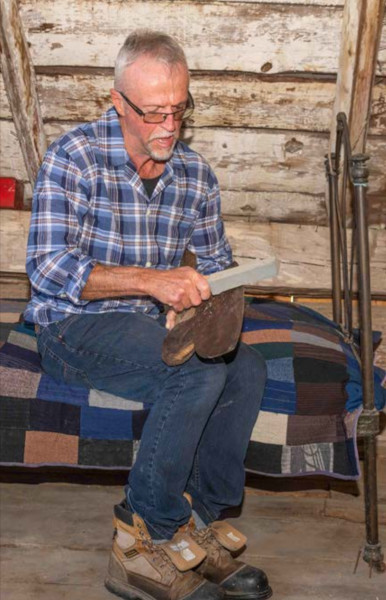

The first task was to build a dwelling on cleared land before winter. In the early townships opened to settlement, sawn lumber was often not available, or too expensive. Rather, the surrounding forests offered trees just waiting to be cut down, squared (or not) and assembled. All that was needed were a few pairs of arms, a few axes and some know-how.

By the 1852 census, the Kilcoyne-Sweeney family were living in a small log house, known as a cabin or “shanty.” Early dwellings were modest, built mainly of logs, and usually about 320 square feet.5 They rested directly on the ground, or on a simple base of stones. The term “shanty” signified that these shelters were built in a hurry.6 “Shanty” may also derive from the Irish “seantigh,” meaning a makeshift cabin or old house.7

The shanty would have only one room on the first floor, used for cooking, eating and family life. A table, a few benches or chairs, and a chest were usually the starting furniture.8 The only ornaments would be some family portraits and religious items, such as a crucifix.9 The upper floor was usually two bedrooms, for the parents and for the children.

In that same census, the Kilcoyne-Sweeney family reported 8 of their 100 acres under cultivation, producing 80 bushels of potatoes (4,800 pounds), 40 bushels of oats (1,360 pounds), and 28 bushels of wheat (1,680 pounds). Their livestock consisted of three pigs, two milk cows and one ox.

Once their first dwelling was completed, the family would have had the daunting task of clearing their land and producing enough of a harvest to satisfy the family and their livestock’s food needs.10 In the early years, it would be difficult to keep livestock, with the priority being growing enough crops to feed their families over the winter. At least in the early days, they could look forward to a winter job in a logging camp, to earn a little money until their land could produce enough to support their families. It was a hard life, but they evidently brought with them a great deal of courage, determination and perseverance, which were probably their greatest assets.

Settlers had to work the soil by hand, using mainly a hoe, because plowing or harrowing was almost impossible until the tree stumps were removed. At best, the ground was simply stirred up with a rough drag, which was at first only a heavy uneven branch or the top of a tree.11 In the early years, they had to cultivate between the stumps, which were left to rot before removal. That took about 10 years for beech and maple stumps, and about 15 years for pine, elm and hemlock.12

Having roughly tilled the land, the settlers could then sow their seeds, in soil that was luckily generous. While the seeds emerged, grew and matured, the settlers would continue clearing their lots. Their occupation licences forbade them from commercially selling cleared timber until their letters patent had been issued, unless they had obtained a specific licence to do so. Until settlers had their letters patent, they could use the felled trees only for their own use—for firewood, for the construction of buildings and fencing, or for making potash.

The timber merchants’ lumberjacks had preceded the settlers, and, in most cases, skimmed the lush, centuries-old forests of their most majestic trees. This was likely the case in the Township of Low during the 1830s and 1840s, since the associates Hamilton and Low were established in the area and carried out logging operations there.13 These merchants took only the species that were in greatest demand: white pine, red pine and oak. Once done, they would abandon the timber limit and move on to another one.

It appears that the Township of Low had been subject to more intensive exploitation of its finest pines than the other townships along the Gatineau River.14

Cutting down and handling these huge trees was a monumental job, and the settlers had limited tools and little experience with trees of this size. This meant the removal of the biggest trees by the merchants made the settlers’ clearing job easier and faster. The disadvantage was that losing such prime trees deprived settlers of a valuable source of income. Nonetheless, they still had to fell the remaining trees, gather the trunks and branches into piles, and set fire to them (sometimes making potash as a side benefit). One wonders if this quotation, translated from a 1919 publication,15 reflects the feelings of those early pioneers: “Each blow of the ax resounded in his mind like a note of hope.”

In spite of these very difficult conditions for settlement, the population of the Township of Low tripled in the course of the 1850s.

For the township, 1854 was an important year: on February 1, Caleb Brooks opened the first post office, which went on to operate for 22 years.16 The arrival of postal service no doubt reduced the loneliness, and made it easier for these newcomers to communicate with relatives and friends left behind in their home country.

Then, on January 1, 1857, the Municipality of Low was officially formed. The act came into effect a year later, with official proclamation on December 1, 1859. Only days later, brothers Robert and John Hamilton, sons of the late George Hamilton, the timber merchant who was associated with Charles Adamson Low, were the first to be granted letters patent by the Crown for 680 acres of land.17

In the early 1850s, in spite of the poor road conditions, William Patterson offered the first stagecoach service between Bytown (Ottawa) and North Wakefield (now Alcove), transporting passengers and mail. From there, brothers Marshall and George Brooks of Low took over, providing the stagecoach connection to the Desert River (Maniwaki). This service constituted a vital link between the various communities in the Valley; a journey over the entire route took about five days. Stagecoaches stayed until the 1890s, when the new train service took over.

These were the conditions, obstacles and challenges that these courageous Irish settlers faced in the mid-19th century, when they left their homeland and arrived in the Gatineau Valley in the Township of Low. In spite of everything, they managed to tame their new host country, become acclimatized to its harshness, and take root, with many of the original settler families remaining for generations.

Martin Lamontagne’s book The Story of an Irish Pioneer Family, Low, Quebec – 1850–1925 is available in English and French. It also includes an overview of the Outaouais’s history before settlement started in the 1800s, acknowledging the millennia of Indigenous presence, then details the early settlement of the Upper Gatineau Valley. The author invites anyone interested in learning more about his research and book to contact him at martinlam111@gmail. com.

Footnotes

- The townships north of Low were not enumerated in 1852, even though some were starting to be inhabited.

- Of these 50 families, nine lived in Range 1 along the Gatineau River, 13 in Range 2, and 10 in Range 3; 18 other families lived on unsurveyed land. Note that the surveying of the Township of Low was not yet completed at the time of the 1852 census.

- Census 1851–1852, Township of Low, Library and Archives Canada.

- The baptism likely took place at the mission of St. Joseph of Wakefield (Farrellton), which was part of the Parish of St. Stephen (Chelsea) at the time. The parish priest, Father James Hughes, probably registered the event in the register of the Parish of St. Stephen simply because there was no register at that time for the mission of St. Joseph of Wakefield. Source: Mgr. J. Marcel Massie, Le Développement des paroisses-souche dans l’archidiocèse de Gatineau, Part 6, 2012, p. 42.

- This was one of the conditions of the occupation licence, granted to settlers by the Crown in order to occupy a lot. The holder committed to [translation] “build a habitable house of at least 16 feet by 20 feet” in the first four years. Source: Jean Hamelin and Yves Roby, Histoire Économique du Québec 1851–1896, 1971, p. 175, footnote 23.

- Census of Canada 1880–81, Government of Canada, Volume 1, p. IV.

- Michael McBane, John Egan, Pine & Politics in the Ottawa Valley, 2018, p. 62.

- Alexis de Barbezieux, père, o.f.m., Capucin, Histoire de la province ecclésiastique d’Ottawa et de la colonisation dans la vallée de l’Ottawa, 1897, Volume 1, p. 284.

- Louis Taché, and others, Le Nord de l’Outaouais: manuel répertoire d’histoire et de géographie régionales, 1938, p. 211.

- Guillaume-Alphonse Nantel, Notre Nord-Ouest Provincial: Étude sur la Vallée de l’Ottawa, 1887, p. 15.

- Edwin C. Guillet, The Pioneer Farmer and Backwoodsman, 1963, Volume 2, p. 29.

- J. E. Garon, Historique de la colonisation de la province de Québec de 1825 à 1940, 1940, p. 36.

- This is consistent with the statement made by Gunda Lambton in her article entitled “The Battle of Brennan’s Hill,” Up the Gatineau!, Gatineau Valley Historical Society, 1981, Volume 7, p. 21: “The Brooks sons divided the good farm land, previously cleared of bush by two men, Hamilton & Low, …”, as well as the article entitled “The Brooks of Low – 1859” in Don Kealey’s book, Low Municipality – Reflections of the Past, p. 515.

- Report of the Commissioner of Crown Lands, of Canada, for the year 1857, 1858, p. 117.

- Mgr. Louis-Adolphe Paquet, Études et appréciations: Nouveaux mélanges canadiens, 1919, Volume 4, p. 340.

- Carol Martin, “Low Then and Now: A Salute to 150 Years,” Up the Gatineau!, Gatineau Valley Historical Society, 2009, Volume 35, p. 6.

- Lots 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 and 33 in Range 1, on the shore of the Gatineau River. Source: Jean-Chrysostome Langelier, Liste des terrains concédés par la Couronne dans la province de Québec, de 1763 au 31 décembre 1890, 1891, p. 749.

References

Geggie, Norma, Wakefield revisited, Castenchel Editions, 2003.

Geggie, Norma, and Geggie, Stuart, Lapêche: A History of the Townships of Wakefield and Masham in the Province of Quebec, 1792 to 1925, Historical Society of the Gatineau, expanded edition, 1980.

Hale, Grete, and Hale, Reginald B., “Brooks Hill – Low, Québec, Canada – Built 1859,” Up the Gatineau!, Gatineau Valley Historical Society, 1990, Volume 16.

Kealey, Don, Low Municipality – Reflections of the Past, self-published, 2015.