- HomePeopleFoundersPeople of NoteStoriesTransportRoadRailRiverLoggingThe CutThe DriveSocial ImpactCreditsMemories Work Bees up the Gatineau

Farming is a pretty lonely job as you are usually doing something like cutting hay or plowing by yourself. For certain farm activities, several farmers would join together and help each other, and throughout the year there would be several bees at each farm. There was sawing in late winter or early spring, then there were the grain and the corn to bring in at harvest time, and every so often a new barn or building would bring everyone together again.

Saw Log Time

During the winter, my father, Arthur Brown, would have to cut the firewood. The wood furnace that heated the big farmhouse was located in the cellar, and consumed great blocks of wood too heavy for me to lift. About twenty-five face cords would be used to heat the house each year. It was never as cozy as today’s homes, but no one froze to death and frozen water pipes were not a worry as we didn‘t even have them.

During the winter, my father, Arthur Brown, would have to cut the firewood. The wood furnace that heated the big farmhouse was located in the cellar, and consumed great blocks of wood too heavy for me to lift. About twenty-five face cords would be used to heat the house each year. It was never as cozy as today’s homes, but no one froze to death and frozen water pipes were not a worry as we didn‘t even have them.

The kitchen stove was the real glutton, having to do all the cooking yearround. The kitchen was also the informal gathering place. Everyone would sit around in the winter, either reading, sewing or repairing harnesses. Occasionally, when a young farm animal needed extra care, it would be placed behind the warm stove. The family had to take turns bathing once a week in a big tin tub with water heated on the stove. The stove also had a water tank from which you could dip hot water at any time. My old Aunt Maud always had her chair where she could get her feet up on the oven door. Uncle Ferguson had his rocker between the stove and the wood box. He was always accused of letting the stove go out if Maud had her back turned.

The process of cutting firewood was both fun and tedious. The first part consisted of cutting down about 300 trees and skidding them up with either a single horse or a team. Usually two men would work at this. The trees were limbed up but left in about twelve-foot lengths. The cut trees were assembled and loaded on a skid or sleigh and moved to an area close to home. A large load at noon, and another at the end of the day, would move all the day’s work to the growing pile at the farm.

After all the trees were gathered and put in an orderly pile, a sawing bee would be organized. The saw was a large round blade, around 36 inches in diameter, and it was run by a pulley and axle that was connected to the power taken off the farm tractor with a belt about ten feet long. The saw had about six feet of table on the “on” side and a couple of feet on the “off” side. As a log was placed on the table the men would rock the table back and cut off the blocks. Some of the logs were so large that they could not be cut through, so they had to be turned. My Dad carried a large scar on the back of his hand due to one careless moment. I suspect others may not have been so lucky as to escape with just a scar.

The farmers, of course, had to do their own chores before the bee started so the bee did not begin until around nine in the morning. Usually the milk cows would be dried up at this time of the year so there would be no milking, only feeding and cleaning. Four men would take a log off the pile and carry it to, and hold it on the table. Once enough blocks were cut off, the two men at the “on” side could take over. On the “off” side one man moved the block away from the blade to be taken by another man and thrown on the pile. Every couple of hours the saw and tractor set up would have to be moved back to try and keep them close to the shrinking pile of uncut logs. The sawdust pile was continually kicked out from underfoot.

At noontime there were eight or nine hungry men. The noon meal was actually called dinner and consisted of meat, potatoes, root vegetables and the ever-present apple or lemon pie. My mother and Aunt Maud never found it a problem to cook for these gangs. The men smelled of fresh sawdust and green wood. Mixed with the food, the smells were wonderful.

The bee always took a couple of days, during which everyone got a turn at each different position, except for the two men on either side of the saw blade. That position seemed to be kept for the experienced men—they were the ones who knew how to place the log so as not to jam the saw, and they sensed when the blade was dull or if the belt was slipping. The young men only got to carry logs and pitch blocks.

After the sawing was done, one of the most boring jobs began. The pile of blocks, from three hundred trees, had to be split with an axe. We would have to take the block and set it up, split it in four or more pieces, throw those pieces over on the other side, again and again, for several weeks. All I can say about it is that it was good exercise.

Harvest Time

In the summer the haying was the first crop done and it continued over a few weeks with hired help because it was not something that could be done in one day. Thrashing, however, was. The oats would be ripe about mid-August. They would be cut with the binder, and we would move in afterwards and take six sheaves, individual bundles about the size around of a shopping bag, and stand them up in little house shapes called stooks. Gloves had to be worn because thistles could be mixed up in the grain.

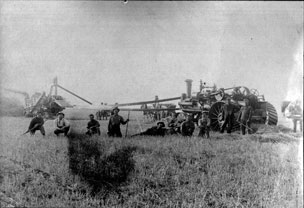

a chance to be with each other c.1920.

The work bee was a fun event as it gave farmers When the stooks were dry, meaning no rain, the thrashing began. Mr. Baldwin or Mr. Meredith would come with a huge machine and tractor and set up in the barnyard. Other farmers would come with their teams and wagons, or later tractors and wagons, and start to load in the field. A tractor team took an extra man, as someone had to drive. The teamster could direct the horses verbally as he built the load.

Loading was always a competition. A good man could attack a stook the right way and get all six sheaves on his fork, pick this up and lift it over his head into the wagon. There would be one man loading either side of the wagon and one man placing the sheaves properly on the wagon. There would be three or four wagons on the go depending on how far they had to haul. The younger men were always anxious to test their strength, so they had contests to see who could load the fastest. This annoyed the older men building the load, as they could not keep up. The load had to be built properly or it might fall off on the way from the field to the yard. That was a reflection on the load builder. Back in the yard, the operator kept his eye on the equipment—greasing this, adjusting that, putting stickum on the drive belt. As the new load pulled up beside the thrasher, the machine would roar to life.

In the modern machines the sheaves were fed right in headfirst. Older machines required someone to cut the binding string. The oats would come out of one long pipe, which was worked by the bagger. This man’s job was to put a jute bag under the chute and fill it to about eighty pounds, then take that bag off and repeat the process. Two men would take turns carrying the full bags to the granary and dumping them in the bins, adding boards as the bins filled up. Meanwhile, the thrashing machine would be blowing the straw up into the loft. A couple of men would be up there moving the straw around to distribute it fairly evenly. They were the most interesting men to see at wash-up. It was hard to believe that anyone could be so dirty! Just white teeth and runny eyes.

At dinner we would have about a dozen men to feed. The wash-up was always fun. Benches and basins of water were set up outside and occasionally the garden hose was used, leading to many water fights, but everyone was just happy to cool off.

As the fall approached, in mid-September it was time for the corn harvest. Not all the farms grew corn, but the ones that did always had silos to store it. The first step was cutting the six- to eight-foot high rows of corn. This was done with a corn binder which had a long nose that reached out and down and cut one row at a time, tied it in a bundle and spat it out behind to be picked up later in the day

My father would have to set up the corn blower. This was a great machine that had numerous stove pipe attachments that had to be erected up the side of the silo to the very top, capped by a hood to point down into the silo then some more pipes coming down inside the silo. The silo itself was round, about sixteen feet across and made of tongue-and-groove wood. It was 30 feet high and had a series of bulkhead-style doors that were in an enclosed area connecting the silo to the barn. There was also a ladder inside the silo so you could climb up to the top door.

In the fall, the fields were pretty wet, so there was always the possibility of getting stuck with a big load of corn. To prevent this the loads were taken from two parts of the field—the heavier bottom half from the wet part and the lighter top part from a drier part of the field. Loading the corn—usually by hand and not with a fork—was often wet work and the corn was heavy, awkward and slippery. However, it was fun to unload into the corn blower with a conveyor chain and slat table that fed the great sheaves of corn into the high, revolving, enclosed combination fan and knife, much like a rotary lawn mower on its side. The chopped-up corn was blown up the pipe, around the hood at the top and back down the pipe inside where you could walk around and direct the pipe as you packed and filled the silo. The bulkhead doors were put in as needed and lengths of pipe inside removed until the whole silo was full.

There were only two things you had to avoid. One was not putting the corn on the machine too fast or you would plug up all the pipes. If this happened, it would take half an hour to clean them out. The other thing to avoid was keeping yourself out of the machine; loose clothes could easily pull you in. We later learned of a third precaution when a farmer and two of his sons were killed by poisonous fumes that can be produced in the silo. Lots of ventilation was required.

To me the corn harvest was the toughest of all the different bees. You were always cold, wet and muddy. But on the positive side, it was rewarding to see the organization work so well, and see the field emptied and barns full. It was like so many things that our ancestors, the settlers here in Canada faced. It was a job that had to be done, and so it was!

Ravenscroft, Helen Ditchfield, Two Bees in Meech Creek Valley, Up the Gatineau!, Vol. 21, 13–15

Thrashing

It was late August and I was home from Toronto to visit my parents on their farm on Pine Road near Meech Creek. The name of the village was Cascades, named for the rapids that had been in the Gatineau River before the river was flooded. My mother asked me to look after the meals while she was away representing the Women’s Institute at their annual convention at Macdonald College, at Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue, near Montréal.

A day after Mother left, my father decided to have the bee for the thrashing, as the thrashing machine was in the area doing all the thrashing for the farmers in the Meech Creek Valley. My father announced to me that we would have fifteen extra men to feed the next day. I was all of nineteen and had been taught by my mother to cook, but for a small family!

A menu in the thirties on a Meech Creek farm would consist of: beef stew made with many pounds of stewing beef and lots of vegetables, hot tea biscuits to go with the stew, gravy, mashed potatoes (20 pounds), corn on the cob, large platters of sliced tomatoes and cucumbers, homemade bread, butter, pickles and for dessert, apple and raisin pies and plenty of tea. All but the raisins and tea would be grown on the farm.

A farm workbee c. 1920 Of course you made your own pastry for at least ten pies—five apple and five raisin. These I made the day before as it is a big job firing up the wood range on a hot day to have the oven the right temperature for pies, and it makes the kitchen hot!

So the day arrived and the thrashing machine and men arrived early, after having done all the milking and other chores on their own farms. My father grew wheat, oats and some barley. The grain had already been prepared by the binder, in stooks and tied. It was waiting on wagons in the barn, ready for the men to proceed. The owner of the machine usually brought his eldest son to look after the engine and ensure that things operated well. Three men worked in the mow, throwing out the sheaves to two men at the table of the machine. The two men at the table each had different tasks: the first had to cut all the binder twine, and the next man fed the sheaves into the machine. It took two men to pile the straw, which remained. Another two men worked to place the burlap bags for the grain coming out of the machine and carry these heavy bags away for storage—they put the younger men on that job because it required strength. That was a total of eleven men, along with older boys who came to help and enjoy the day and the food. The thrashing machine owner was paid $10 to $12 for four to six hours work, and from this he supplied the gasoline for the machine and operated it.

The wheat was used for flour to feed us; it was ground at the MacLaren gristmill in Wakefield. Dad also had cracked wheat ground at the mill; it made wonderful bread and porridge. The oats were used to feed the horses, cows, pigs and chickens. The barley was used to make great lamb stews and soups.

Thrashing can be a dusty job so the farm wife was expected to have plenty of water, soap and towels ready for wash-up time. I remember that we filled a tin bathtub with water and put it on a table in the sun outdoors to warm for washing up, and we also used hand basins.

So everyone ate heartily. My Dad said I did a good job and I was relieved when my first catering job ended.

The Winter Wood Bee

The farmers in the Meech Creek Valley had bush lots, some of which were quite a distance from the farm. Usually after Christmas my father and brother would prepare to go to the bush lot to bring home the logs for the March sawing bee. This provided all our stoves, fireplace and furnace with wood. They would leave with the bobsleigh and team of horses, with their noon lunch and cut trees all day, returning around four in the afternoon with their load of “poles,” logs up to about 12 inches in diameter.

After many trips to the bush, the pile of poles would grow big enough for our future needs. Hard work! There were still all the other chores to do before day’s end, too. When the “bee” day arrived, my Dad would arrange for the man with the sawing machine to come and word would go out to the neighbours, the Ditchfield wood bee was on. Each neighbour who came had the favour returned when he was ready for his bee.

The sawing bee usually took place in March, with snow still on the ground. Four men were needed at the log pile, taking turns carrying the “poles” to the table of the sawing machine. As with the thrashing machine, the machine owner would operate his machine, assisted by one of his sons, and was paid for it. Two men worked at the table of the sawing machine to move the poles along; this was dangerous work with the big saw operating! Two men at the other end caught and threw the cut pieces off into a pile. The wood came through quite fast. So there would be at least ten men, as well as the older boys who came to help and enjoy the day and the good food. After the logs were cut, the farmer and his sons had to hand split all the cut logs into stove- and furnace-sized pieces, pile it, and dry it for a year. Then they would have to go through the whole routine again the next winter. Life in the thirties was challenging and fun. How green was my Meech Creek Valley.

Brown, Jim, Up the Gatineau!, Vol. 21, 8–12.